Photography

Historically, photography has played an important role in forensic medicine and science. The records of the Department of Forensic Medicine (GUA FM) contain numerous photographs, photomicrographs and lantern slides which were taken by the police and members of the department, and utilised by them for teaching and research purposes. These include photographs of victims, productions/evidence, and crime scenes.

The third edition of John Glaister Senior's Text-Book of Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology, published in 1915 contained hundreds of photographs, taken by himself or at his request. Glaister was sceptical about the application of Alphonse Bertillon's anthropometric system created for photographing criminals. Glaister stated that:

In regards to the identity of criminals was accompanied by means of written descriptions, with respect, among other things, to bodily defects and markings, along with photographs. A glance however, over a few pages of a criminal 'album' will suffice to show how valueless the latter were for the purpose, since the knowing criminal had only to throw his features into some grotesque shape to vitiate the intended result, which was, moreover, commonly done. It could not, therefore, be pretended that these means were scientific.

John Glaister Junior succeeded his father as Regius Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Glasgow in 1931. He, like his father was greatly interested in photography. Glaister wished to improve the department's teaching and laboratory facilities. He purchased ultra-violet lamps, cine-cameras, and equipment for colour photography. Glaister was also interested in the possibilities of using ultra-violet rays and X-rays in the detection of crime.

Photographic Evidence

|

Ref: GUA FM/2A/25/118 Policemen preparing evidence from the Ruxton case to be photographed |

|

Ref: GUA FM/2A/25/119 Police photographer taking pictures of evidence from the Ruxton case |

Photomicrography

|

In their book entitled On Soul and Conscience, published in 1988, M. Anne Crowther and Brenda White noted that:

|

|

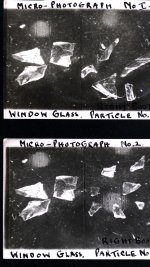

Ref: GUA FM/2A/28B Microphotographs of glass found at the scene of a house breaking, 1934 |

Identification

|

James Couper Brash produced some pioneering work on photographic superimposition in the case against Dr Buck Ruxton in 1935. Brash matched anatomical landmarks from skulls with facial features from photographic portraits, in order to positively identify the remains of two women who had been brutally murdered and disfigured. This photographic work was well documented in Glaister and Brash's book entitled Medico-Legal Aspects of the Ruxton Case, published in 1937. |

Publications

- Bertillon, A. (1889) The Identification of the Criminal Classes by the Anthropometrical Method (London: Spottiswoode & Co.).

- Bertillon, A. (1893 ) Identification Anthropométrique: Instructions Signalétiques (Melun: Impr.).

- Crowther, M.A. & White, B. (1988) On Soul and Conscience: The Medical Expert and Crime (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press).

- Glaister, J. (1915) A Text-Book of Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology (Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone).

- Glaister, J. Jnr. & Brash, J.C. (1937) Medico-Legal Aspects of the Ruxton Case (Edinburgh: Livingstone).

- Rhodes, H.T.F. (1956) Alphonse Bertillon: Father of Scientific Detection (London: Harrap).